Palace park

The area of the palace park had been an integral part of the mountainous landscape for centuries. Ordinary arenas of the Károlyis’ (or their tenants) and the serfs’ farming activities were the arable lands, meadows, cabbage gardens, orchards, woods, cart paths and springs. This condition changed during the 1850s. Ede Károlyi, who was working on the reconstruction of the palace, dreamed of an upscale park around it, following the fashion of the era. The area, formerly of agricultural and forestry importance, had become a romantic English park in a decade. Hills, valleys, springs, and flowing waters were given new roles. The significance of the space from then on was determined by the experience of looking at the palace and the view from the palace itself.

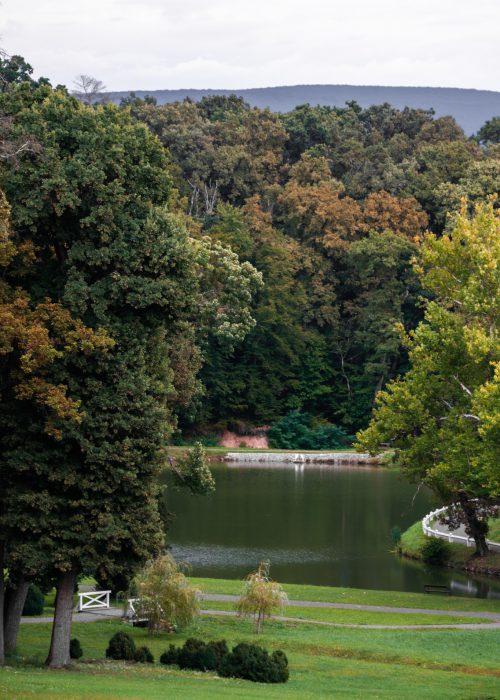

The mountainous landscape provided excellent conditions for the construction of an English, i.e. landscape park. The Pajna Hill and the Korom Mountain, the water washes and clearings around the palace made it become the most picturesque Károlyi estate. To further strengthen its picturesque character, the former terraces were made to be more sloping, clearances were cut in the woods, new roads were created and ornamental plants were planted next to the native trees and shrubs. It was during this period that the famous plane trees, which have now developed into giants, were planted along the banks of the brook. A few old horse chestnut trees near the palace are of a similar age, and the Paulownia tree, planted at the same time, has since grown two new seedlings. The two most spectacular elements of the transformed landscape are the fishpond created by the construction of a dam, and the sparse pine allee that can still be seen today, for which the count himself had the pine seedlings brought from France. In addition to the pálinka (“fruit brandy”) brewery and the stables, some new outbuildings were built in the park. These included a small building called Banquet House on the hill above the village, which served both as the home of the vineyard guard and a viewpoint as well.

However, the agricultural role of the estate, which was placed in the service of the aristocratic way of life and hospitality, did not disappear completely, it only shifted in the landscape. The former apple and plum orchards were relocated farther away from the palace. A smaller orchard, with some old varieties in it, can still be found in the section of park by the village.

The first gardener of Füzérradvány estate identifiable by name was István Czapáry. The beginning of his entry into service is unknown; perhaps it dates back to the early 1840s. He must have been working in Radvány by 1846, and until he left in 1857, he was one of the key figures in the design of the English garden. He worked not only as a gardener but also as a principal administrator during this important time in the history of the palace. Some important landscaping work can be linked to his name in the park, such as the construction of the fishpond dam and perhaps -either in part or in whole- the design of the landscape garden too. He may have taken an active part in the planting of ornamentals, such as the plane trees that can still be seen today, as well as in the design of the decorative courtyard and new roads. As an administrator, he presumably played a major role also in the development of Vilyipuszta. Not only were they breeding cattle and burning brick there, but a number of factories ensured the viability of the estate as well. The estate administration centre was moved here too. This is how the reconstructed palace along with its surroundings, including the parish church of the village, could become the field of aristocratic representation. At the time, the church was already embraced by a black pine plantation, which felt like a park, and its altarpiece contained references to the “mythical” events of the founding of the new era.

In the autumn of 1857, Czapáry was followed by Joseph Paradieser of Austrian or Moravian descent, maintaining the park for half a century, still according to the concept dreamed up by Count Ede Károlyi and István Czapáry (and perhaps Miklós Ybl), in the first few decades.

The palace and with it the park was rethought during the time of Count László Károlyi, at the turn of the 20th century. The plans, which were in contrast with the former romantic English character of the park, were drawn up by the famous French gardener of the age, André Edouard, and then supplemented by the new chief gardener, Ferenc Zinke.

The two main directions of the transformation of the park were to enhance its “subalpine” character and to rethink the ornamental gardens surrounding the palace. The image and use of the park were fundamentally changed by the construction of the serpentine road that still exists today, necessitated by the spread of vehicular traffic. To enhance the natural experience, rocks were built into the wall of the new deep road, and rock garden plants were planted among them. The subalpine features of the landscape, which were later sought to be emphasised in the commercials of the palace hotel, developed thanks to the newly planted pines. Although the environment was not fundamentally suitable for trees living in high altitude areas, the count and his gardener were both passionate about spruce, fir, Douglas-fir, and silver pines. Therefore, many specimens of these were planted during this period, even if not as many as László Károlyi -not taking the tolerance of alien species into account- would have liked. This topic was often the subject of debate between the count and his gardener.

There are still traces of the two geometrically constructed garden parts, which were made according to the fashion of the age. The French garden, designed on the southern side of the palace, required significant landscaping: the upper part of the steep hillside was filled and levelled, creating an artificial terrace.

The trendy historicising garden, which can be considered as an extension of the palace, included some previously planted sycamores and horse chestnuts that had to be slightly cut back. New ornamental plants were added to the garden, among them a maidenhair tree (ginkgo biloba) and a cut-leaved linden tree can still be seen in the immediate vicinity of the palace.

By the time the first decorative trees, planted in the era of Ede Károlyi began to age, the role of the park also took a significant turn. With the opening of the palace hotel, Count Ede’s grandson, István Károlyi, put the park itself at the service of distinguished hotel guests too. For the guests, not only the aristocratic splendour of the palace but also the modern sports facilities were an attraction. Accordingly, the most spectacular developments of the period were the holiday house pavilions, the ski and golf course and the lido.

Some of the activities promoted in the palace hotel ads were not unprecedented in the landscape. It had been possible to go hunting, on long walks, horseback riding and even play tennis before – relatives, politicians, nobles and artists who enjoyed the hospitality of the former counts made use of these facilities.

However, the new tourist fashion that emerged in the 1930s, required new types of leisure activities in addition to the 19th-century ones. Therefore, a sledge run was established in one of the line clearances and a golf course in another, and the slope of the Pajna Hill served as a ski resort in winter.

The biggest and most expensive investment was the lido. This also adversely affected the picturesque nature of the park, which was previously intended to be natural, so it is understandable that Ferenc Zinke, the park’s chief gardener at the time, vehemently opposed it. Next to the pool, a pool house designed in the style of folk architecture was erected, where guests could get changed. It was possible to take the sun – to sunbathe in a contemporary expression – in a clearing that had become a “lido meadow”. The park, therefore, developed into an empire serving hotel guests looking to relax, in every possible way.

The area has always been a land of waters. The palace used to be surrounded by springs and brooks, and six bridges crossed its rivers. They already started to put natural waters in the service of the palace and its inhabitants in the middle of the 19th century. The Tuzinka spring, for instance, supplied water to the three bathrooms of the count’s suite, to the fountain, and even to the lion’s head gargoyle that still exists today. Already in 1855, Count Ede Károlyi had a two-room bathhouse built next to the fishpond made by blocking the brook, in order to make Radvány attractive to his wife and little daughter, favouring and spending time in various spas. The marble bathhouse built on the basement level of the palace, which was also supplied by the water of the spring, served the same purpose.

The unparalleled ancient woodland embracing Károlyi Palace has been a nature reserve since 1975. The pride of the more than one hundred-hectare arboretum are the plane tree giants that have survived the storms of history. Among the largest specimens in the country are these centuries-old ancient trees on the banks of the brook. With its wide-spreading lime trees, multi-trunked tulip trees and pyramidal English oaks, the palace park, which almost melts into the woods of the area, is one of the most unique historical gardens of Hungary, with an unmatched atmosphere. Fishponds, romantic bridges across brooks, shady groups of trees and a fairytale-like woodland tempt you to walk here for hours. Visitors can also admire the huge park surrounding the palace from the top of the restored lookout tower.